When COP28 starts on November 30 in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, no less than the future of climate finance provision will be front and center throughout negotiations.

When this year’s UN climate summit (COP28) will convene in Dubai end of November, no less than the future of climate finance provision under the climate regime will be negotiated across the agenda, and with it the issue of equity and whether the obligation of developed countries to support developing countries with new and additional, adequate and predictable funding to urgently scale up climate efforts still holds or whether the move from multilateralism to voluntarism accelerates. Significant pledges by developed countries in Dubai for the initial capitalization of the new Loss & Damage Fund despite rejecting any historical responsibility and obligation to provide support will be the clearest litmus test.

Fundamentally a matter of shoring up trust and regaining momentum in the international climate process, this comes as the first ever collective assessment of progress in implementing the Paris Agreement, the Global Stocktake (GST), concludes at COP28 with a sobering accounting of the shortfall in global efforts to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees. Rapidly scaling up the quantity and quality of climate finance is inextricably linked to scaling up the ambition of actions over the next five years until the next GST. With 2023 likely to be the hottest year in recorded history, a never ending string of devastating extreme weather and climate events around the world, and worsening indebtedness of ever more climate vulnerable countries, COP28 under the incoming presidency of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) must set markers for providing new and additional finance for fast-tracking a transition to renewable energy, for safeguarding peoples’ lives and livelihoods in response to compounding climate impacts and for helping them recover and rebuild from already devastating losses and damages.

The agenda behind the COP28 Agenda

Even before negotiations formally start, several proposals for new agenda items focused on contentious issues around climate finance could lead to a protracted agenda fight – and thus potential stalemate at the very beginning of the two weeks of climate talks. The agenda proposals pit developed countries’ interest to discuss the alignment of all finance flows with goals under the Paris Agreement more broadly (such as through a new agenda item on Article 2.1 (c) proposed by the EU), against developing countries’ interest to uphold the principles of equity and common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities (CBDR-RC) as the basis for the implementation of the Paris Agreement, thus applicable for all related climate finance negotiations (by asking for an agenda item on operationalizing CBDR-RC with respect to Article 2.2). Developing countries also might request additional agenda items on the promised doubling of adaptation finance and on urgently scaling up support to enhance the ambition on mitigation action, while the United States might ask for an agenda item on the review of the financial mechanism (and related entities and obligations) under the Paris Agreement. Defusing this negotiation mine field will be an early test for the climate diplomacy skills of the COP28 Presidency.

Operationalizing and capitalizing the new Loss & Damage Fund

A core element of a Dubai package deal for COP28 will be the approval of recommendations for new funding arrangements to address loss and damage, and most prominently, a governing instrument for a new Loss & Damage Fund. Those were adopted only in early November as part of a ‘take-it-or-leave-it’ package in a last-minute effort to avoid a failure of the eight months long process under the Transitional Committee (TC), which was mandated by COP27 in Egypt to present consensus proposals to COP28. The compromise, which concluded the TC's mandate, left both developed and developing countries dissatisfied for different reasons. Developing and developed countries clashed on many issues, chief among them the location of a Fund as either a standalone institution or housed under the World Bank and who should pay primarily into the LDF, as well as which countries would be eligible to receive support. The final text, which placed the new Fund for an interim period of four years under the World Bank, while safeguarding that all developing countries could draw on its resources, revealed deep divisions: developing countries pushed for recognition of developed countries' historic financial responsibility, while the latter, especially the United States, insisted on voluntary contributions only. Despite concerns from developing nations about the lack of commitment for a significant scale of the Fund and developed countries’ financial inputs, the text was adopted in the spirit of compromise, leaving unresolved issues for the future Fund Board to tackle. Nevertheless, this outcome likely sets a problematic precedent in the ongoing struggle for consensus and commitments in global climate finance negotiations.

The contentious issue of funding sources for the new Fund dominated discussions throughout the TC process, reflecting broader debates about the future of developed countries' financial obligations under climate agreements. Despite developing countries’ insistence on language acknowledging historical responsibility and differentiation in contributions, the final text adopted a neutral stance, urging support on a voluntary basis and significantly weakening the differentiation between developed and developing countries' contributions. This outcome, seen as a retreat from previous financial commitments, raises concerns about the adequacy of funding for the new Fund and its operationalization. The is a significant risk that the new Fund remains under-resourced despite its establishment under the World Bank, which was used as a justification by developed countries for this placement arguing that it would maximize potential financial contributions to the new Loss & Damage Fund.

The United States, initially refusing to agree to the TC outcome package at the TC’s last meeting in early November in Abu Dhabi, has since indicated a willingness to accept the compromise, reducing the likelihood of reopening discussions in Dubai. Other countries also expressed reservations, but the TC's package approval suggests a comprehensive revision is unlikely at COP28. To improve the TC outcome, some parties may instead aim to incorporate relevant language into other COP28 decisions, addressing finance provision mandates and the scale of the new Fund, both missing from the TC outcome package and crucial for climate justice. Meaningful commitments to the Fund's initial capitalization at COP28, such as the EU's recent signal that it will provide a ‘significant contribution,’ could help ease continued developing country distrust and concern, although a similar indication is lacking from the United States, and rifts among developed countries, on how to handle financial support for loss and damage, seem to be widening .

Global Stocktake – global finance needs and realities

Maybe the single most important outcome of COP28 will be the decision to formally conclude the first Global Stocktake (GST). This is the main accountability process designed under the Paris Agreement to assess every five years whether the bottom-up commitments under countries’ nationally determined contributions (NDCs) and related implementation actions in the aggregate are on track with the goals of the Paris Agreement and to provide the forward-looking push to ratchet up ambition over the next five-year period. The reality is sobering: as the UNFCCC’s most recent NDC assessment report highlights, under current NDCs, global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are set to increase 9 percent by 2030, compared to 2010 levels. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has been clear that emissions must fall by 45 percent by the end of this decade compared to 2010 levels to meet the goal of limiting global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees.

In order to achieve the peaking of emissions before 2030, as the report argues, developing countries’ access to finance, technology and capacity-building, the ‘means of implementation’ (MOI), which the GST also assessed and found sorely lacking, must be massively increased. The NDCs of most poorer countries are conditional on such support, especially public finance to be provided by developed countries. According to the GST assessment, public finance support “remains a prime enabler for action”, in order to supplement efforts that developing countries can undertake with domestic resources alone, giving their shrinking fiscal space. Over the past decade, the number of developing countries in severe debt distress has grown to now 59, the majority low-income countries and among the most climate vulnerable countries globally. In light of the worsening and unsustainable debt levels of developing countries, the ability of most developing countries to finance necessary climate investments is severely restricted without addressing the debt-climate spiral through debt relief to allow for inclusive and just transformations.

However, it is yet still unclear whether and to what extent the GST decision will highlight both the role and the continued obligation of developed countries to provide public finance to ramp up collective global ambition. A draft structure of the decision still shows any reference to finance in GST recommendations bracketed, with options showcasing developing countries’ effort to stress the link between public finance provision and their ambition, while developed countries try to shift the focus away from their finance support mandated under the Convention (in Article 4) and Paris Agreement (in Article 9) to broader references to the need to make all financial flows consistent with the goals of the Paris Agreement under its Article 2.1(c).

Overall financing climate finance needs are massive and in the trillions, and the longer climate investments are delayed now to reduce emissions and address already occurring severe impacts, the higher the costs will be in the future, especially to address rapidly escalating and compounding loss and damage. By some estimates, up to US$ 9 trillion per year is required until 2030, more for the period 2030 to 2050. This compares with roughly US$ 1.3 trillion, or roughly 1 percent of global gross domestic product (GDP) that according to an analysis by the Climate Policy Initiative (CPI) was flowing in climate finance in 2021/2022 (aggregating all climate investments, public and private, in developed countries and in developing countries and North-South climate finance transfer flows), although this increased significantly over previous years. Some 90 percent of this finance was for mitigation with strong increases in the renewable energy and transport sectors, with just 5 percent each for adaptation and cross-cutting efforts combing both mitigation and adaptation elements. This, as well as the uneven distribution of available climate finance across regions and country groups – developed countries committed 84 percent of international climate finance, while less than three percent went to Least Developed Countries (LDCs) – highlights the crucial and continued importance of public finance provision from developed to developing countries as part of continued efforts to address these imbalances and inequities.

The US$100 billion goal – elusive no more?

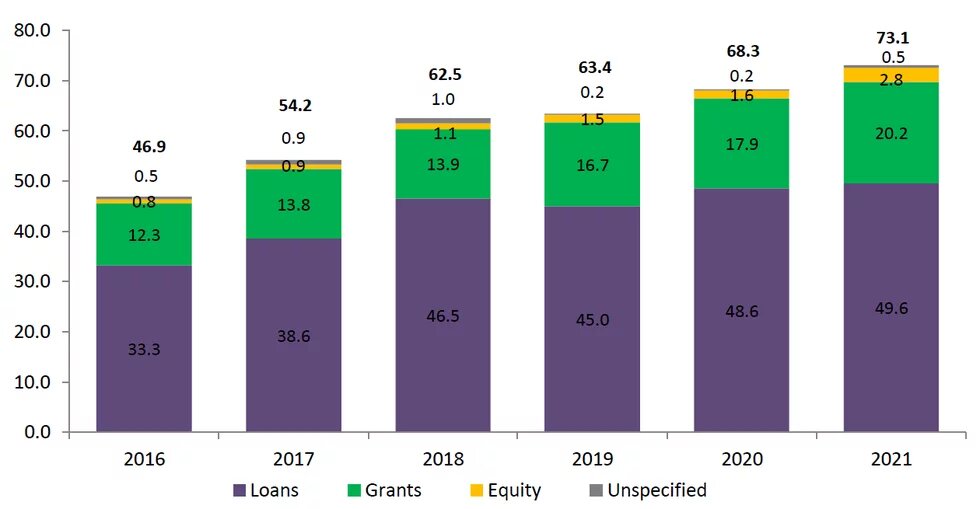

In climate finance, one reason for the distrust by developing countries in developed countries’ willingness to uphold their end of the Paris Agreement grand bargain for collective climate action is the continued failure by developed countries to deliver the US$ 100 billion annually by 2020 as promised in a goal politically set, and already then inadequate, in 2009 in Copenhagen. According to newest OECD figures just released, while not reaching the mark yet, in 2021 climate finance flows from developed to developing countries increased by 7.5 percent (or US$6.3 billion) over the previous year to reach US$ 89.6 billion (see graph 1). The OEDC also estimates that according to preliminary data the US$100 billion goal might be finally met in 2022. For Canada’s Environment and Climate Change Minister and Germany’s Special Envoy for International Climate Action tasked by the Egyptian COP27 Presidency in July 2021 to outline a climate finance delivery plan, this is good news. In an open letter they point out that “this amount exceeds the forward-looking scenarios for 2021 released two years ago by the OECD” and improves upon their own earlier estimates.

Graph 1: Climate theme of climate finance provided and mobilized in 2016-2021 (in US$ billions)

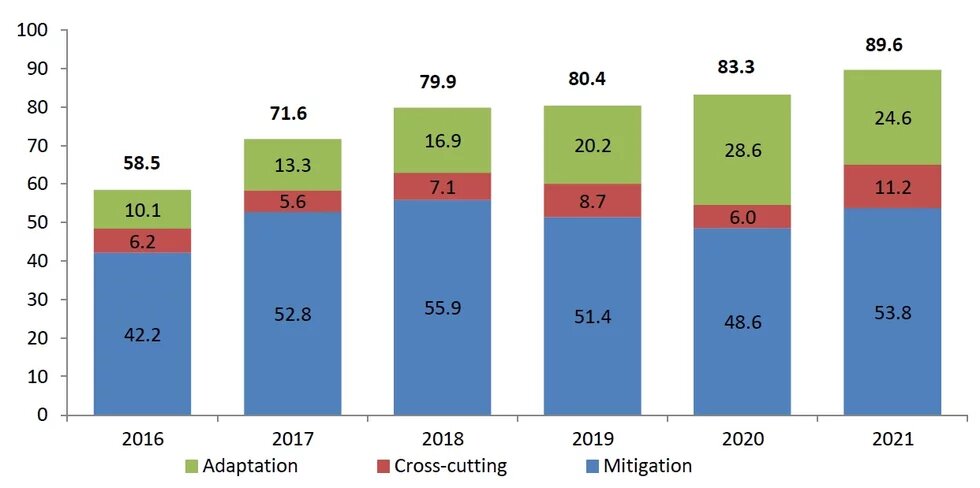

However, the record is more mixed and far from reason for jubilation. Firstly, even if the goal was reached in 2022, there is still a multiyear shortfall (US$16.7 billion in 2020 and US$10.5 billion in 2021), which developed countries would have to compensate to get to the US$100 billion average over the 2020-2025 period, until a new climate finance goal currently under negotiation kicks in. Secondly, while the share of grant financing increased to roughly 30 percent, this mean with two thirds the vast majority of public finance is still provided as loans, increasingly untenable, even at concessional rates, for most developing countries (see graph 2). Lastly, and distressingly, developed countries’ climate finance provided for the poorest countries and population groups fell in 2021 compared to the previous year, reversing an upward trend since 2016. LDC’s share of climate finance dropped to 20 percent from 25 percent in 2020, while around US$ 4 billion less was provided for adaptation in 2021, despite the overall finance growth, lowering adaptation’s share of public climate finance mobilized and provided to just 27 percent (see Figure 2). Most of this finance continued to be provided as loans in the main sectors of adaptation measures, accounting for 71 percent of climate finance for adaptation in water supply and sanitation, 59 percent in agriculture, and 78 percent in disaster preparedness. The adaptation finance drop was due in large part to less money for adaptation from bilateral agencies and multilateral development banks (MDBs), while adaptation finance provision through multilateral climate funds increased, where the delivery as grants is significantly higher.

Graph 2: Instrument split of public climate finance in 2016-2021 (in US$ billions)

Falling behind on adaptation finance

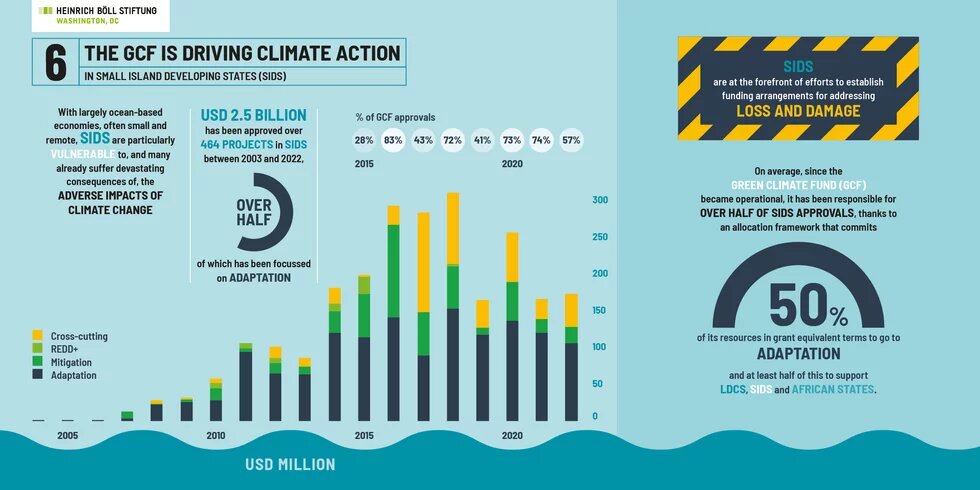

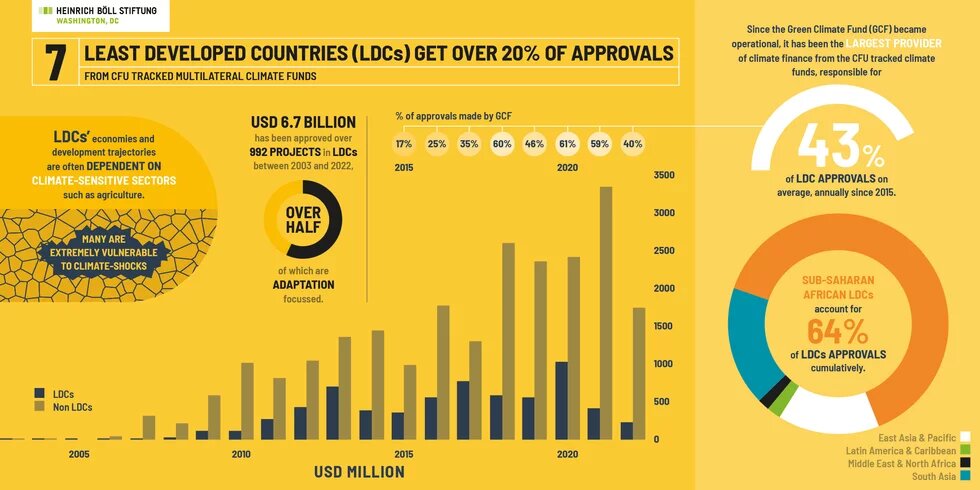

The OECD figures showing adaptation finance at US$24.6 billion in 2021 after US$28.6 billion in 2020 are discouraging, as they showcase that the promise of developed countries in the Glasgow Climate Pact to double adaptation funding from 2019 levels by 2025 to US$38 billion is not on track. Using a different methodology, Oxfam’s Climate Finance Shadow Report 2023 puts the grant-equivalent value of adaptation finance in 2020, and thus the climate-specific net assistance provided to developing countries, even lower at just US$10.6 billion. Both sets of numbers are reflected in a report by the Standing Committee on Finance (SCF) on doubling adaptation finance mandated at COP27. It stresses some of the challenges in disaggregating climate finance numbers by theme, including extrapolating the adaptation finance share of cross-cutting activities, which further increased in volume in 2021. Using 2019-2020 figures, the report highlights that MDB provided the majority (83 percent) of their adaptation finance as loans while bilateral sources provided 57 percent of adaptation finance through grants. In contrast, almost all adaptation finance from multilateral climate funds was delivered as grants. This once more highlights the difference in the provision of core public climate finance through multilateral climate funds under the UNFCCC and Paris Agreement, including the Green Climate Fund (GCF) or the Adaptation Fund, and in line with core principles of equity. In 2019–2020, of the total adaptation finance from multilateral climate funds, the LDCs received 38 percent compared with their 26 percent of total climate finance, and small island developing states (SIDS) received 21 percent compared with 7 percent of overall climate finance. In the GCF, their share was even higher (graphs 3 and 4)

Graph 3: Importance of the GCF for climate finance flows to SIDS

Graph 4: Importance of GCF for climate finance delivery to LDCs

Of particular relevance is the GCF as the largest multilateral climate fund due to its allocation framework that provides for balanced allocation between mitigation and adaptation in grant-equivalent terms, and ringfences half of its adaptation finance for LDCs, SIDS and African countries. However, its October pledging conference under the GCF’s current second replenishment has been underwhelming, garnering so far only US$9.3 billion, and thus less than the US$ 10 billion during the first replenishment, instead of the doubling that civil society has asked for. Thus, the pressure will be high on the COP28 Presidency to deliver increased adaptation finance as part of its overall push for progress on the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA), and on developed countries to announce substantial new finance pledges, including to the GCF and especially those by countries that have yet to do so (including most prominently the United States, but also Switzerland, Italy, Sweden and Australia).

The adaptation finance provided – and its trajectory – fall way short of what is needed. According to the recently released UNEP Adaptation Finance Gap Update 23 report, which is based on costed adaptation need articulated in 85 NDCs and National Adaptation Plans (NAPs), the average adaptation finance required for all developing countries for the timeframe 2021 to 2030 amounts to an estimated at US$387 billion per year, with the adaptation financing requirement for LDCs and SIDS estimated at US$41 billion per year.

As many adaptation measures need to be locally focused to provide benefits to affected communities and people, and barriers to accessing climate finance for adaptation remain high for many of the most vulnerable countries , simplifying and enhancing access, must be a focus of discussions both on the GGA and on adaptation finance. This includes providing direct access by devolving funding decision-making to communities and marginalized groups and individuals in a human-rights centered and gender-responsive way by applying the principles for locally-led adaptation (LLA). The LDC Group has committed to a target of channeling 70 percent of climate finance to the local level by 2030 through a focus on more LLA.

Setting a new need- and science-based climate finance goal

While no final decision is expected at COP28, in Dubai the three-year negotiations on setting a new collective quantified goal on climate finance (NCQG) to be met from 2025 onward with one year remaining will enter from the technical phase (with so far seven of expected twelve expert dialogues completed) to the highly political phase of agreeing on the goal. Fundamental differences between countries are not of a technical nature, but strike at the heart of climate finance provision guided by equity and CBDR-RC and its continued relevance. In Dubai, a high level ministerial dialogue is supposed to provide guidance on how a final outcome in 2024 could be structured and the negotiation steps to get there over the remaining year. Developing countries are determined to ensure that the NCQG addresses the existing shortcomings in both quantity and quality of the politically determined US$100 billion goal by ensuring that the new goal is based on science and developing countries’ needs. Two years ago, the SCF detailed in its first ever needs determination report funding requirements in the trillions to implement developing countries’ NDCs, many of which are conditioned on financial support, as well as NAPs. And IPCC reports on mitigation and adaptation and loss and damage have stressed the scientific basis of enormous financial needs.

A new NCQG will have to be substantially higher, secure public finance provision as the core, and also address questions of scope, quality, timeframe and accountability of and increased access to climate finance, not the least by incorporating finance to address loss and damage as the third distinct financing pillar besides mitigation and adaptation and ideally setting thematic public finance sub-goals. Civil society observer argue that such sub-goals should reflect the grant-equivalent value (reducing loan provision and addressing debt) and be regularly reviewed, ideally in sync with the GST. Developing countries see the need to sharply focus on the quantum of the goal as the basis of determining its component elements in the remaining negotiation time. In this context, the lack of a uniformly accepted multilateral definition of climate finance is a shortcoming that developing countries wish to be addressed, while developed countries feel that a bottom-up approach to defining climate finance is acceptable, as long as its parameters are transparently disclosed. At COP28, the SCF will present its continued work on improving the operational definition of climate finance, integrating submissions it received from countries. While discussing the scale of the new finance goal in Dubai, developing countries will hone in on the obligation of developed countries under Article 9 of the Paris Agreement to take the lead in providing public financial support. Developed countries aim to frame the NCQG discussion in the wider context of the mandate under Article 2.1(c) of the Paris Agreement and want to expand the group of contributors to climate finance provision to developing countries, such as China or Saudi Arabia that they argue are in the financial position to do so. Article 2.1(c) puts the focus on making all financial flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate resilient development, and thus would minimize the relevance (and presumably the scale) of developed countries’ own public finance contributions for the new climate finance target to be set in 2024 while pointing to the private sector to provide the trillions needed and the importance of regulatory approaches, green taxonomies and enabling environments.

Article 2.1(c) and Article 9 and their complementarity

The relationship between Article 2.1(c) and Article 9, both central to the discussion about finance for the implementation of the Paris Agreement, and the question which article can be seen as complementing which, is at the heart of the discussions about the NCQG. Already for COP27, developed countries had pushed for an agenda item on Article 2.1 (c). This failed, leading to a likely renewed attempt for COP28. Instead in Sharm El-Sheikh, just a one-year work program on making all financial flows consistent with the Paris Agreement was approved. COP28 is expected to extend and formalize this work further. A mandated report by the SCF to be presented at COP28 highlights fundamental differences between developing and developed countries on how to implement Article 2.1 (c), noting that there is no shared understanding even on the scope of the article’s ask. Developed countries argue that any climate finance discourse must center on mobilizing the private sector to get to the large scale of finance required for tackling climate change and point to the role of domestic and international regulatory efforts in shifting finance flows away from climate-harming investments (including for ending fossil fuel subsidies). They see climate flows under Article 9, which relates to the provision and mobilization of financial support to developing countries, as contributing to the broader financial shift. Developing countries have been skeptical of these efforts, fearing they are a way to substitute or diminish developed countries’ obligations under Article 9. In their view, broader financial flows are separate to and must be complementary to developed countries’ climate finance delivery to developing countries, especially since private sector actors and many initiatives to shift financial flows have little to no accountability under the Convention and the Paris Agreement, while parties do. They stress that common but differentiated responsibilities of developed and developing countries apply to all types of climate flows, arguing that developed and developing countries should have different obligations and timelines for addressing emission-intensive, including fossil fuel activities and investments, based on their different socio-economic circumstances and challenges. Developed countries’ efforts on green taxonomies and regulations, including the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanisms (CBAM), are perceived as endangering developing countries’ right to development tailored to national and local needs.

Safeguarding climate finance under the UNFCCC

Under the Convention and Paris Agreement, there is no enforcement or accountability mechanism to compel financial actors and initiatives outside of the UNFCCC climate process to enforce consistency and compatibility with climate goals, as evidenced in the ongoing debate around the role of Article 2.1 (c) and also brought into sharp focus in efforts to craft recommendations for new funding arrangements to address loss and damage. In reverse, while the UNFCCC processes might not be able to influence those actors, they nevertheless shape the way climate finance discourses in the climate regime are conducted. 2023 saw many ongoing processes of relevance for the future of climate finance under the Convention and Paris Agreement, chief among them discourses on the reform of MDBs and their climate-relevant finance support, concrete proposals presented by the Bridgetown Initiative, the World Bank Evolution Roadmap process and the Summit for a New Global Financing Pact hosted by the French government. At least in part the targeted focus on further expanding the role of MDBs in climate finance as well as creating additional initiatives separate trust funds (such as the Global Shield) is driven by developed countries’ preference to engage in climate finance discourses and fora where they hold a commanding position (such as through the shareholder governance in MDBs or in plurilateral efforts such as Just Energy Transition Partnerships).

As the importance of such actors and initiatives outside of the UNFCCC grows, whose climate finance delivery is not aligned with core principles of equity and CBDR-RC under the climate regime, it is important to at least safeguard the relevance of public climate finance provision through UNFCCC multilateral climate funds, and ideally to a concerted push to expand them. COP28 is an important opportunity to regain some ground in this effort. This will depend on several crucial decisions being taken in Dubai to operationalize the new Fund to address loss and damage, conclude the Global Stocktake with forward looking mandates to increase climate finance as a conditional means to more ambition in implementation, chart progress toward a substantially higher new climate finance goal to be set at COP29 next year. COP28 must also garner significant pledges to support the ongoing second replenishment of the GCF as well as jump-start the initial capitalization of the new Loss & Damage Fund.

This article first appeared here: us.boell.org